Can the human spirit truly be broken?

- Ana Maria Phkhaladze

- Aug 6, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Sep 16, 2025

“Freedom is the freedom to say that two plus two make four” (Orwell 81). With this quiet yet powerful declaration, Winston Smith in the novel “1984” reminds readers that even under totalitarian rule, the human spirit continues to fight and reach for truth. But what happens when truth is erased, identities are stripped, and even memory becomes dangerous? Can the human spirit survive under such conditions? This question has been asked through both dystopian fiction works and history, and the answer, while not simple, is one we keep returning to: the human spirit bends, but it doesn’t easily break.

The same pattern applies to dystopian novels like George Orwell’s “1984” and Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale,” which reflect the lived experiences of people under authoritarian rule. Governments may control faces and bodies, restrict choices, rewrite facts, and history. Still, there always remains a stubborn force within the people that resists — a quiet opposition, a whisper of hope, a memory that continues to live. That’s the human spirit.

George Orwell’s “1984” offers a haunting portrayal of a society where the ruling Party, under the ideology of “Ingsoc” (Orwell 6), employs strong psychological manipulation and surveillance to dominate not only public behavior and “Freedom of Speech” but private thoughts too. Slogans like “War is peace. Freedom is slavery. Ignorance is strength” (Orwell 3) are not mere contradictions, but deliberate tools to shatter logic and condition obedience. Yet this dystopian vision is not limited to fiction only. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (U.S.S.R.) under Joseph Stalin similarly sought control over both reality and memory through “Cult of Personality” propaganda, surveillance, and “Red Terror”. Those who glorified the leader as infallible, while state-controlled media and plugs silenced dissent. Like “The Party” in “1984”, Stalin’s regime didn’t just demand obedience — it demanded honest belief and trust towards the government.

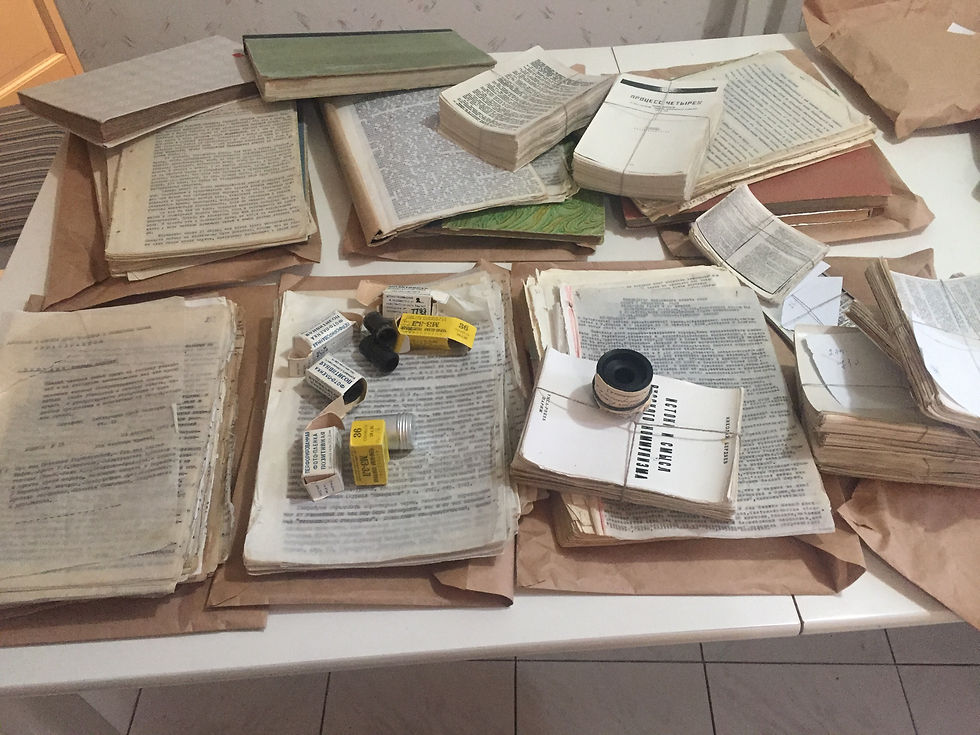

Despite all the intensity of such control, cracks in the system revealed a deeper truth: the human spirit does not surrender quietly. Underground publications like “Samizdat” (самиздат — Self-Publishing), their whispered songs, and the careful preservation of censored books all became acts of refusal to obey the abusive system. Similarly, in modern-day China and North Korea, where authoritarian governments monitor digital communications, control media, and suppress free expression, individuals still find a way to oppose and fight back. Human Rights Watch on December 21, 2023, reported the documents on how protestors use encrypted messaging apps, digital anonymity, and secret networks to protest censorship and communicate truth (Human Rights Watch). Those real-life examples and facts imitate Smith’s furtive acts of rebellion in the Orwellian world — writing forbidden thoughts in a forbidden diary, falling in love with Julia, questioning the laws, social structures, and official narrative. Though small and often crushed, such acts of defiance signify an enduring human impulse: to claim inner freedom even when the other freedom is lost.

Russian samizdat and photo negatives of unofficial literature.

The synthesis of Orwell’s imagined dystopia and historical or ongoing records shows a shared strategy, that totalitarian control operates not only through force but through the invasion of personal truth and individuality. Yet, what the cruel regimes cannot fully destroy is the human capacity to remember, to question, and to hope. Winston’s spirit appears broken by the end of the novel, but his earlier defiance represents a universal human tendency towards refusal to be fully erased.

On the other hand, Margaret Atwood’s novel “The Handmaid’s Tale” explores a slightly different setting, where women’s identities and morals are systematically erased and replaced with state-assigned roles. Offred, the protagonist, is stripped of her official name and fundamental autonomy, reduced to a reproductive vassal in the theocratic society of Gilead. Yet her resistance remains, lying in memory, identity, and inner belief — the quiet acts that preserve her sense of self. “I tell, therefore you are” (Atwood 279), she says, insisting on the power of narrative as rebellion. Offred’s self-defiance, though not outwardly revolutionary, is a refusal to obey against your will.

This non-loud but very powerful form of resistance is demonstrated today in the movements led by women under the oppressive regimes. For example, in Iran, following the death of Mahsa Amini in police custody in 2022, women began removing their hijabs and cutting their hair publicly as a symbolic, deeply personal act of protest against mandatory forced dress codes and various institutional gender oppressions (National Public Radio). These protests sparked ongoing movements where women continue to risk imprisonment or much worse by sharing banned and censored books, using social media, and chanting anti-government slogans in the streets. In Afghanistan, where the Taliban has once again barred females from attending school/ educational centers and banned women from most public roles, many young women defy these laws by running underground schools and distributing educational materials in secret (Amnesty International 2024)

Just like Offred, they appeared to be silenced in public, but their private choices became significant acts of protest, not with guns and weapons, but with education, intelligence, memory, and pride. The parallels between Atwood’s fiction and these contemporary examples highlight a truth that transcends time and place: even when visibility and voice are taken away, the human spirit ,especially in women long targeted by authoritarian structures, always finds ways to speak, and to fight back. Survival, in such cases, is not mere existence but a form of moral resistance.

Still, some argue that the human spirit can be completely crushed. After all, millions perished in concentration camps and gulags. Many gave in — emotionally, mentally, spiritually — to the unbearable weight of cruelty and despair. Yet even in those darkest corners of history, objections emerged, not always in rebellion, but in survival and meaning. Viktor Frankl (1905–1997), a Holocaust survivor and psychiatrist, recounts in “Man’s Search for Meaning” how prisoners endured Nazi concentration camps by clinging to even the smallest sense of purpose. He writes, “Those who have a ‘why’ to live, can bear with almost any ‘how’” (Frankl 76). For some, it was the memory of a loved one. For others, it was the dream of bearing witness. Even when autonomy and dignity were nearly destroyed, people found ways to remain human. That, too, is resistance.

Psychological research also supports this. A study by Steven M.Southwick at the Yale School of Medicine (2014) found that resilience isn’t a fixed trait — it is a function built over time. People adapt to trauma by forging meaning, seeking connection, and holding onto beliefs that transcend their suffering. This isn’t just theory. It explains how survivors of war, genocide, and totalitarian rule can emerge with dignity intact. Resilience isn’t heroic in the cinematic sense. It’s quiet. It’s ongoing. It’s a process that needs some time.

So what does resistance look like?

Sometimes, it’s dramatic — like Harrison Bergeron, in Kurt Vonnegut’s dystopian world, who rips off his government-imposed handicaps and cries, “Watch me become what I can become!” (Vonnegut 43). But more often, resistance is quieter. In “1984”, Winston Smith fights back in secret: reading Emmanuel Goldstein’s book “The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism”, talking to O’Brien about joining a secret society, and clinging to an idea of freedom. In “The Handmaid’s Tale”, Offred depends on her memories, her voice, her name, insisting on her humanity by telling her story, even when no one may be listening.

Each of these examples in this paper shows that while systems may dominate externally — controlling speech, dress, even movement — they cannot fully extinguish what happens inside the mind and heart. The will to know, to love, to imagine, and to speak out, however quietly, persists. And that persistence is the human spirit’s ultimate defiance.

Of course, resistance doesn’t always lead to victory. “1984” ends with Winston defeated, uttering “ I love Big Brother” (Orwell 298). It’s devastating. But the fact that he dared to think, to remember, to love remains powerful and serves as a significant symbol for many readers around the world. His loss is a warning, not a surrender. “The Handmaid’s Tale”, by contrast, ends with hope. Offred steps into the unknown. We don’t know if she is freed, but we know her story survives. That survival is the triumph, because memory and truth are weapons against oppression.

Today, dystopia is not fiction. Surveillance exists. Censorship spreads. In many countries, people are jailed or killed for speaking out. LGBTQ+ rights, women’s rights, voting rights — these are being stripped in both democratic and authoritarian nations. And yet, the spirit continues to exist. People write. People speak. People remember.

The human spirit may be bent, silenced, or even seemingly lost — but it is never gone. As long as people continue to hope, to resist, to imagine a better world, the spirit endures. That is what these stories — and our history — teach us. The real question is not whether the human spirit can endure, but whether we will protect it when it is most at risk

Comments